By Beth Mills, MA student at the University of Exeter (2015-2016)

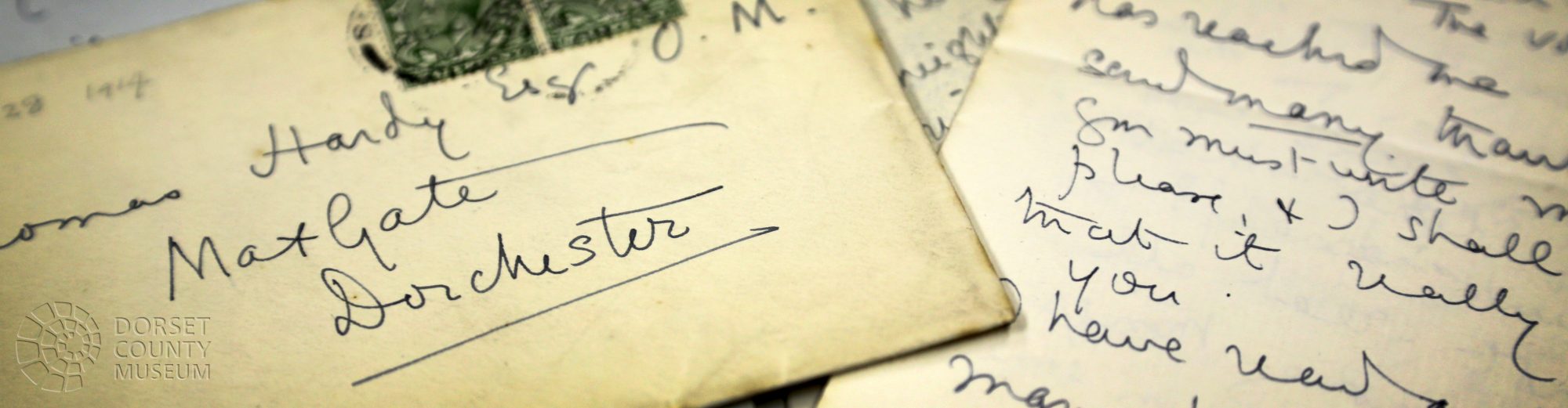

Having had the pleasure to assist as an intern on this project over the spring and summer, I am delighted to be rejoining Thomas Hardy and his acquaintances for the remainder of this year. As the new term begins and I prepare to return to the University of Exeter’s Special Collections, I would like to share some reflections that the experience of working on ‘Hardy and Heritage’ has prompted so far.

Aside from the sheer number of his correspondents, the archive reveals the high esteem in which these individuals held Hardy. Whilst the letters of such notable figures as Florence Henniker bespeak valued friendships, admiration for Hardy and his many fictional works can be found throughout the collection. Given that some of my time spent photographing the letters coincided with that of writing an essay on The Return of the Native and Tess of the D’Urbervilles, I was especially drawn to messages from eager university students, some of whom were writing theses on Hardy’s novels. Undertaking their degrees during the first decades of the twentieth century, these young scholars must have been exhilarated by the possibility of conversing with an author whose reputation was by that point well-established.

Of particular relevance to my own research were two telegrams from the Canadian-born writer of popular fiction and science, Grant Allen. Like Hardy, Allen had attracted criticism for a novel centred on a heroine who diverged from dominant moral codes: Herminia Barton, the Cambridge-educated heroine of The Woman Who Did (1895), eschews established conventions of marriage. Having praised Jude the Obscure (1895) a year earlier, in January 1896 Allen promised to send Hardy a copy of his own controversial work, declaring that “[i]t deals with problems of the time which interest us both” (Telegram to Thomas Hardy). Such windows into the political, social, and intellectual attitudes of Hardy and his contemporaries afford his correspondence dynamism. Through everything from brief comments such as Allen’s to more detailed exchanges on pressing contemporary topics, the archive animates Hardy’s context and paints a rich portrait of the diverse relationships that he sustained through the written word.

Grant Allen

Through an exciting combination of photography and digital encoding, ‘Hardy and Heritage’ unites late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century literary heritage with technologies and research practices of the twenty-first century. It has introduced me to the method of digitisation using the Text Encoding Initiative, along with the challenges that this process entails. As such, the project has been a constant source of intellectual stimulation, as I am confident that the finished database will prove to be for Hardy’s readers and researchers today and for many years to come.