Chrissi Lewes took the ‘Hardy and Women Who Did’ module in her third year at the University of Exeter (2016-2017). Here she shares her insights into using some of the letters from the Hardy archive for her dissertation.

The Hardy and Heritage Project enriched my capacity to research throughout my final year, and access to original letters sent to Hardy gave me a far more intimate understanding of Far from the Madding Crowd – the subject of my dissertation.

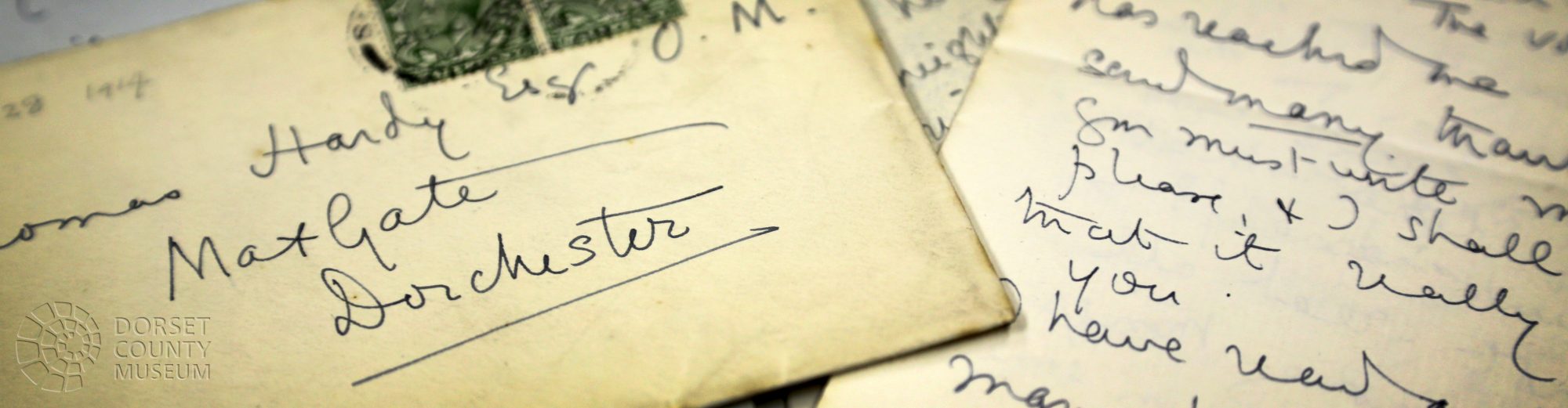

The process of transcribing a letter was challenging (for Victorian writing is beautiful though on occasion illegible), yet akin to unravelling a mystery; with every word being a reminder of stepping back in time and reading the same letter which Hardy opened at Max Gate. These details, coupled with Hardy curiously ripping a page of a letter from Leslie Stephen (Stephen to Hardy 13th April 1894), delicate sign offs which are now obsolete today such as ‘I am yours very truly’ and ‘yours in haste’, as well as esteemed individuals such as Grant Allen expressing his gratitude to Hardy for sending him a copy of the novel, offer a picture of Victorian correspondence. The experience of reading the digitised letters online is equally fascinating, and the underlined hyperlinks helpfully provide additional context.

My experience with the Far from the Madding Crowd collection led me to directly confront the censorship that Hardy grappled with and much begrudged. Hardy’s editor, Leslie Stephen, urged that Troy’s seduction needs to be ‘treated in a gingerly fashion’ (Stephen to Hardy 2nd March 1896), and concedes that he would be ‘somewhat be glad to omit [Bathsheba’s] baby’ (Stephen to Hardy 13 April 1894). My dissertation analysed Crowd in relation to adaptation studies, therefore I was also interested to see that Stephen deemed the novel ‘rather long’, and described that the plot development was too slow for periodical form unless it underwent edits (Stephen to Hardy 17 February 1894).

Yet I learnt that it was not just Stephen that held strong opinions on Hardy’s most published and popularly read work. Katharine Macquoid, a novelist and travel-writer who was similarly concerned with the ‘women question’, wrote to Hardy in order to interrogate Bathsheba’s femininity. Macquoid’s letter reveals that Bathsheba disrupted her perception of a conventional heroine, and, moreover, that of a conventional woman. She wrote:

‘It was ungrateful to find fault with Bathsheba who must have took you infinite times and labours to create – she is almost always true to herself but then her nature is not that of a true woman – because she is centred on the self’ (Macquoid to Hardy 18 November 1874).

Though a handful of words were indecipherable, I felt I had struck gold as I read this passionate piece. It posed a wealth of questions regarding female literary archetypes, the novelist’s world being ‘something much greater than the ‘public’ idea of it’, and it was interesting to see how her ideas on the desired traits of a heroine gradually became conflated with that of women in the flesh. Fritted with dashes, her trains of thought remained incomplete for Hardy to rejoin – indeed, she penned that she could not reach ‘answers without getting into chapters’ (Macquoid to Hardy 18 November 1874).

Overall, the Hardy correspondence collection immediately allowed my research to become more meaningful, and fulfilled my broader interests as I could catch glimpses of Hardy’s character and private life. It is well known that Hardy’s writing created debate through his critique of the gendered and social conventions of his epoch. The collection of letters will visualise this for you, and help you to develop arguments on various aspects of the Victorian public’s engagement with both Hardy and his work.

Chrissi Lewes