While carefully photographing the contents of the N box, I was particularly drawn to the letters and postcards of Lady Dorothy Nevill (1826-1913) – writer, hostess and horticulturist, daughter of Horatio Walpole, the third Earl of Oxford, and correspondent to both Darwin and Hardy.

Illustration of Lady Nevill printed in Vanity Fair, 1912

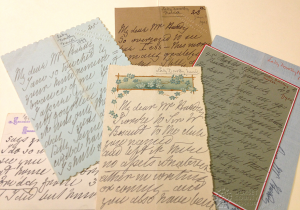

Although there are only fourteen letters from Lady Nevill across a nineteen-year period, the small collection stands out because of its aesthetic appeal. Floral borders and headers catch the eye and an array of different coloured paper make an attractive archive bundle. The Victorian communication revolution resulted in a boom in the range of personal stationery available and Lady Nevill’s choice of notepaper suggests something of both her warm, enthusiastic personality and her passion for horticulture.

A selection of the letters sent from Lady Nevill to Hardy.

After marrying her cousin, Reginald Henry, in 1847 Lady Nevill turned the Dangstein estate in Sussex into a horticultural landmark boasting over seventeen conservatories of exotic plants. In 1861 Charles Darwin wrote to Nevill as a highly regarded orchid grower and she obliged him by supplying various specimens to further his research. Their epistolary exchanges can be read online at the Darwin Correspondence Project , and in due course I hope it will be possible to link data from our digital archive to others, so that a whole network of Victorian correspondence can be rebuilt online.

Nevill’s first letter to Hardy was sent in 1891 after the serial publication of Tess of the d’Urbervilles. In 1892 Hardy gave her a copy of the novel which Nevill valued highly. Her letters indicate that she was one of a number of female readers who wanted to voice their support for Hardy’s honest portrayal of Tess.

It was Lady Nevill’s fondness for Dorset that drew her to Hardy’s work. In Life and Letters of Lady Dorothy Nevill (1919) her son, Ralph Nevill, describes how his mother’s ‘recollections of old-time Wessex rippled as sweetly through her memory as a stream through a pleasant dell.’[1] The biography’s depiction of Lady Nevill riding across the ‘wild country’ as a young girl also seems to cast her in the shape of a Hardy heroine.

Beyond their shared love of the landscape, Hardy and Lady Nevill developed an enduring friendship through her enthusiasm for holding salons at her home. An accessible railway link from London to Sussex brought a large circle of writers, artists and politicians, including Disraeli, to Dangstein and Nevill was one of a number of English hostesses who not only entertained the literati but were also writers themselves.[2]

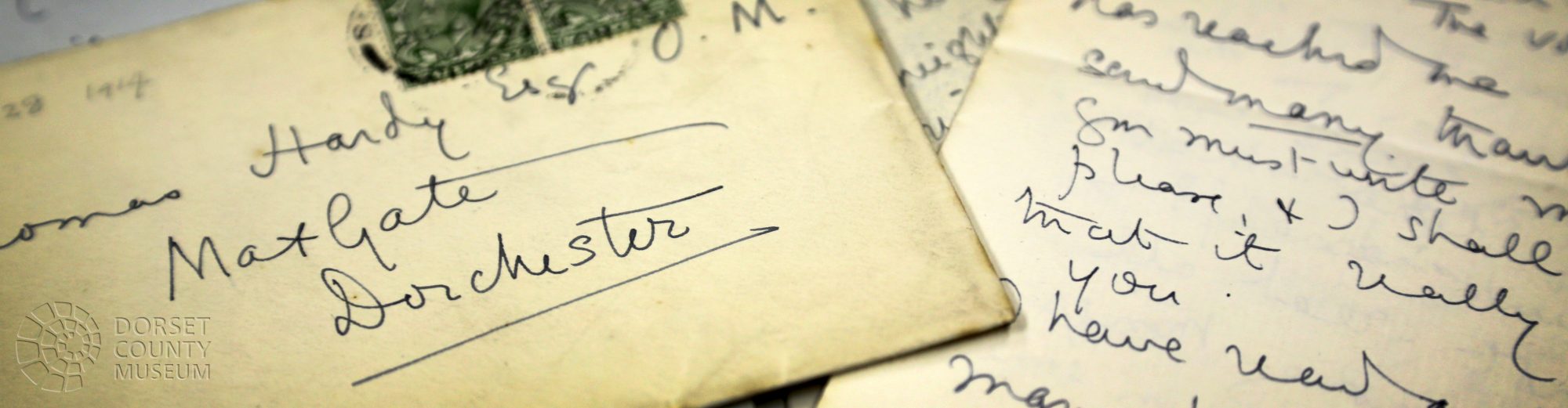

While the transient conversations of the salon are lost in time, evidence of their friendship remains within the pages of her letters which are not only visually appealing but also reveal a playful way with language and a familiarity with Hardy as a valued Dorset friend. One postcard written in 1899 reads:

Dear Mr Hardy,

You have behaved very badly never coming near me but I am a philosopher and forgive you. Will you and Mrs Hardy have luncheon on Saturday the 16th?

Yrs D Nevill

[1] https://archive.org/stream/lifelettersoflad00neviiala/lifelettersoflad00neviiala_djvu.txt

[2] Leaves from the Notebooks of Lady Dorothy Nevill (1907)